![]()

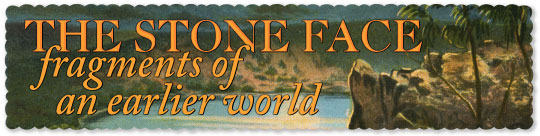

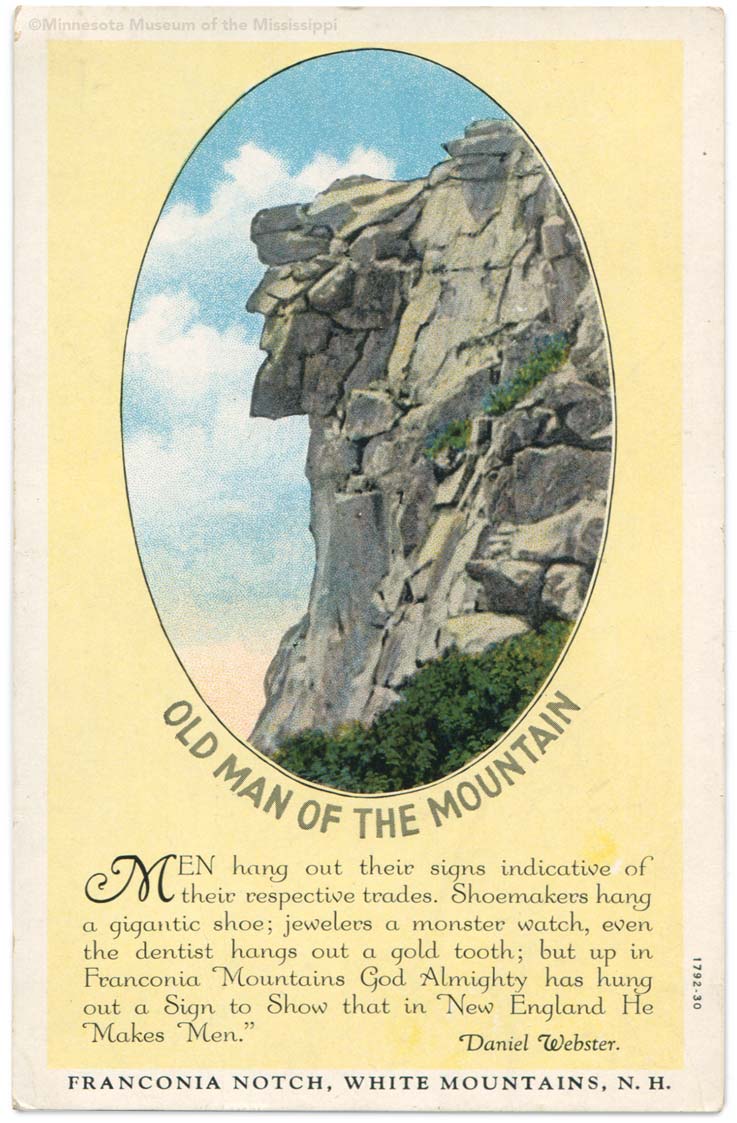

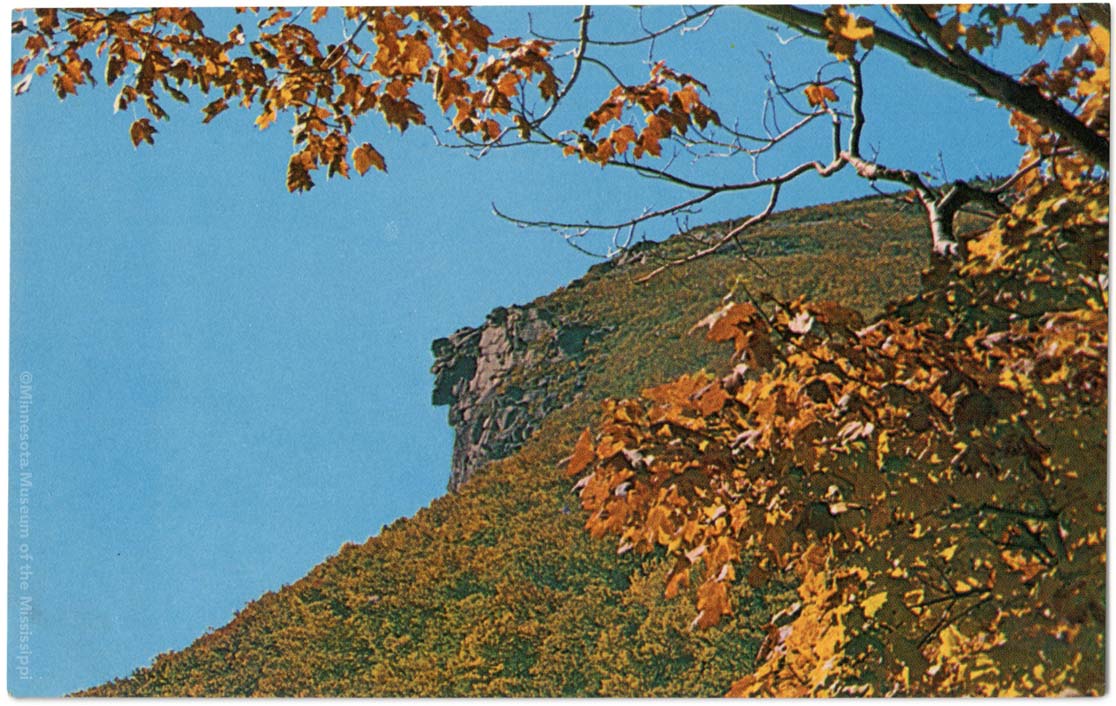

New Hampshire is nicknamed "The Granite State" for its rugged topography of the White Mountains in the north. Here, in a narrow valley scoured by glaciers and walled in by steep rocky cliffs, the most famous stone face of all was discovered in 1805. A survey party laying out a road through this pass through the mountains happened to take note the unusual formation high atop the 1200-foot cliffs on the side of Cannon Mountain. The face could only be recognized by viewing the cliff from the north end of the lake below the cliffs, as it was not a single boulder or outcrop, but made up of five separate ledges of rock which lined up to create an anamorphic image of a face.

Though the aligned image was only visible from one particular viewpoint, this did not detract from interest in the formation as word of its discovery spread among travelers on the newly-completed road through Franconia Notch. Unlike many other stone faces on smaller boulders and narrow canyon walls, this rock profile protruded proudly from the side of a mountain, forty feet in height. With his square jaw and heavy brow the Old Man of the Mountain gazed nobly over the whole valley from his lofty perch. Visitors proclaimed it one of the great natural wonders of America, alongside Niagara Falls as a sublime spectacle.

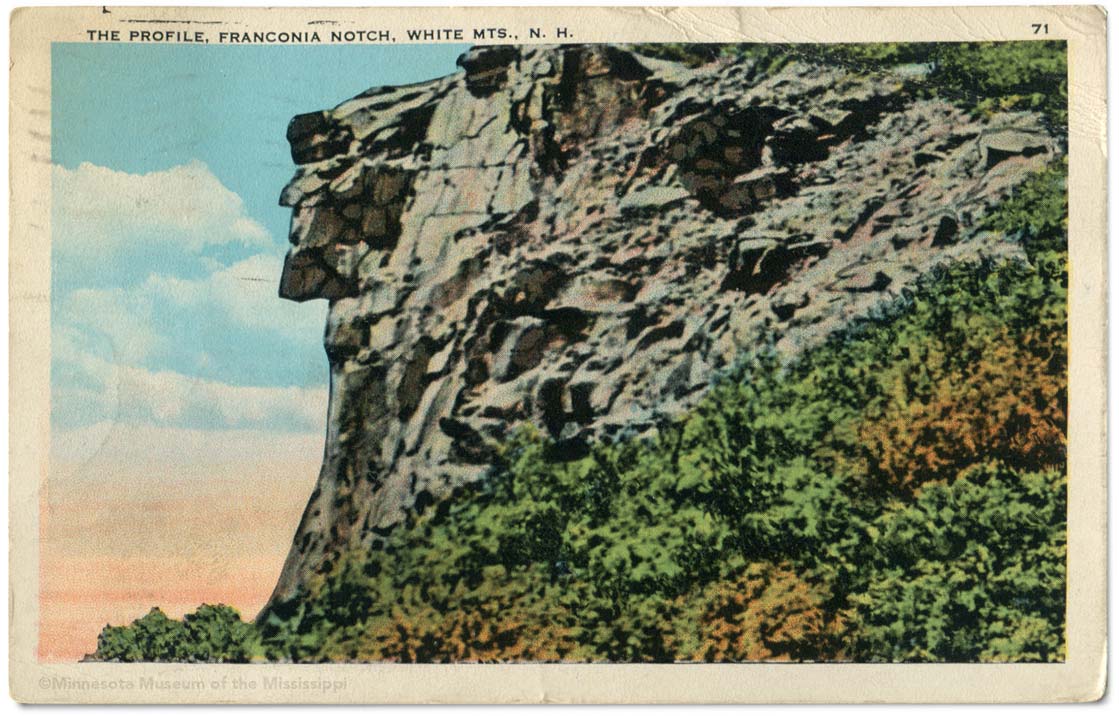

New Hampshire native son Daniel Webster is credited with an often-quoted proverb about the Old Man, that "...God Almighty has hung out a sign to show that in New England he makes men." We assume he meant not men made of sloppily random alignments of impressions, but fully-formed, chiseled men of stony character. Later, Nathaniel Hawthorne continued the theme with his short story "The Great Stone Face" about the steady destiny of a humble farmer who comes to embody the unspoken ideals of the great face.

Hawthorne's story did much to spread word of the face on the mountain. The railroad reached the town of Franconia just to the north of the valley at about the same time in the 1850s, providing easier access to tourists from throughout New England, and the first Profile House hotel was established to house visitors to see the craggy curiosity. The hotel later burned down, twice, but each time it was rebuilt larger than the ashes. Its last incarnation, a 4-story 400-room structure, entertained politicians and big-wigs, celebrities and writers from far and wide before it too combusted into history in 1923.

In 1872, hikers climbing on top of the Old Man discovered the precarious situation of the formation's forehead. The 25-ton boulder was no longer attached to the bedrock but was seen to be gradually slipping forward and indeed the back end of it was hanging dangerously over open air. Concerned citizens below worried that the beloved image might crumble at any moment, but it wasn't until 1916 that Edward Geddes and Rev. Guy Roberts won approval and funding from the state governor to remedy the situation.

From precise measurements, Geddes and Roberts created a scale model of the cliff face and came up with a plan to stabilize it using massive steel turnbuckles. Stalwart climbers carried the disassembled hardware to the top of the mountain and down to the profile piece-by-piece on their backs. Mr. Geddes worked through rain storms and freezing temperatures to hand chisel and drill anchor holes in the granite for attaching the bolts. At last the metal bracing was finished and the structure of the Old Man was secure. Great pins were screwed into the loose boulders of the profile's forehead, and secured to the solid rock behind by the tightened turnbuckles.

Down in the valley below, the state purchased the old Profile House property and 6000 surrounding acres, saving it from the lumberman's axe. Franconia Notch State Park opened in 1928, providing public access for the enjoyment of tourists, hikers and fishermen under the watchful gaze of the Old Man. In 1938 the park built the first aerial tramway in North America, a cable car taking visitors to the top of Cannon Mountain in seven minutes. New Hampshirites of all ages visited the park and came to recognize the familiar visage of the Old Man of the Mountain. In 1945 the stone face was chosen as the official emblem of New Hampshire, appearing on highway signs, license plates and other state documents, including a 1955 postage stamp and the state quarter released in 2000.

Through the seasons of rain, sun and snow, the freezing and thawing of water in the rock continued to erode the stone face. In 1958, workmen returned to the mountain to reinforce the weathered boulders with additional steel cables and ties. They sealed cracks behind the face with cement and weatherproofing to keep out the eroding moisture. What appeared to viewers down below as a nature-made icon of granite strength was actually a fragile symbol held together by man-made intervention.

In the early morning hours of May 3, 2003, the precariously perched boulders finally gave way. The distinctive ledge finally yielded to gravity and the front half of the profile tumbled down to the talus slopes below.

In 2011 the Old Man of the Mountain Legacy Fund dedicated "Profile Plaza" at the north end of Profile Lake. A unique sculpture recreates in miniature the missing stones of the profile. Looking down the side of the sculpture, viewers can align the missing half of the face with the real cliff in the distance, to see what the famous profile once looked like.